The Creative Philosophy Behind the Lomo'Instant Wide William Klein Edition

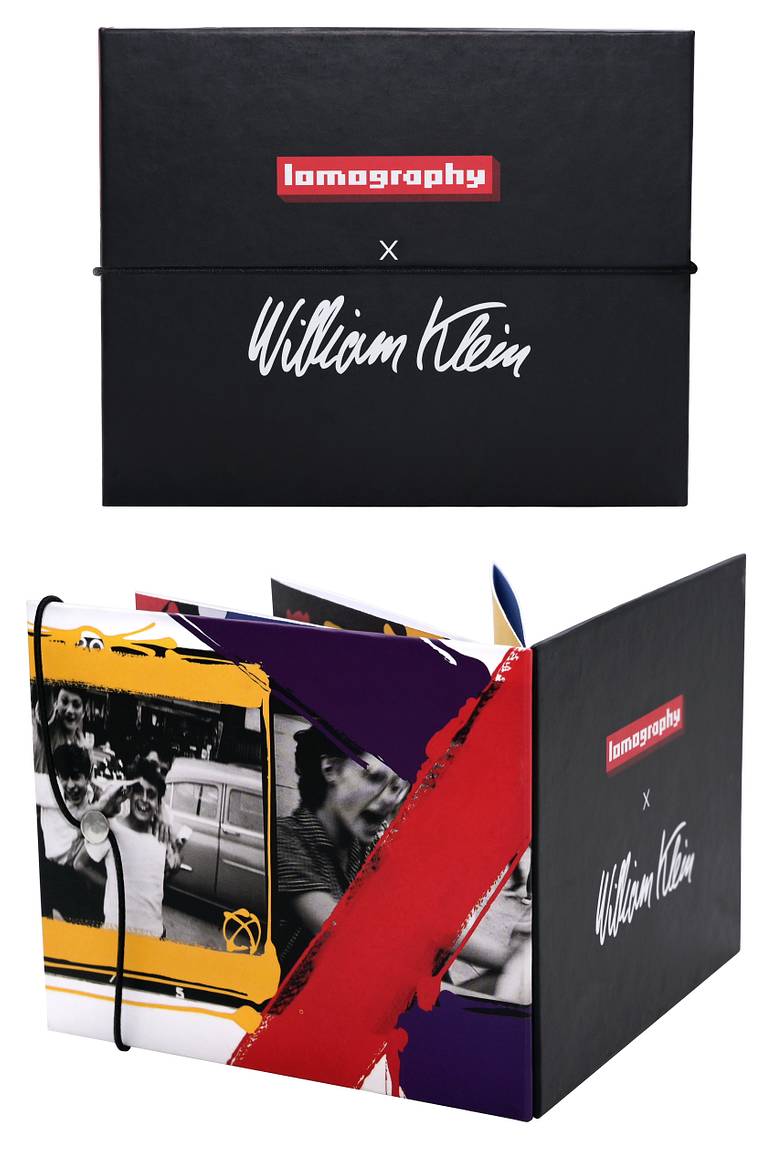

4 26 Share TweetWilliam Klein is known for his aversion to the set rules of photography that led to revolutionizing multiple genres he's worked on. Famed for using wide-angle lenses to produce his iconic imagery, we at Lomography collaborated with the artist and the Polka Factory Paris for the Lomo'Instant Wide William Klein Edition. Through this homage, we celebrate the pioneer's raw, unapologetic, and fierce aesthetics. We sit down with William Klein himself as we learn more about his vision, work ethic, and the philosophy behind the Lomo'Instant Wide William Klein Edition.

Photographer, artist, painter, filmmaker, author... but which one do you feel suits you best?

I couldn’t say. All this describes my work and the things I had the opportunity to do during my career.

You described photography as ‘behind the rest of the arts’ when you first came to it. Can you tell us more about your thoughts on that?

Living in Paris, I wanted to paint. I had the luck to work in Fernand Léger’s studio. Photography only came after.

Could we ask you about your photographic process? Was there a different approach when you shot for Vogue to when you were working on a photo essay?

Of course, it was different. For Vogue, I was hired as a photographer for a commissioned work, with a contract and a payment of a certain amount every month, to produce on behalf of the magazine… So it’s not the same. My more personal research works started with the book New York: Beyond Shooting, it’s all the work on the layout, on the cohabitation, on the relationships between images, that allowed me to express myself in another way.

One of your most recognizable bodies of work is that of your « painted contact sheets ». Could you tell us more about this combination of drawing/painting and photography?

The painted contacts allowed me to analyze the way I approached photography on a 36 frame roll… A thing that intrigued me was this specific “gesture” of the photographer who “marks” the choice of his photos on his contact sheets most of the time with the help of a red pencil. I was interested in the characteristics of these lines, of these reports of choices, of these indications. After all, these photos taken one after another, that we read on the contact sheet from left to right, like a text, it’s the photographer’s diary. What he sees through the viewfinder. His hesitation, his failures. His choice. He chooses a moment, a framing, another moment, another framing. He perseveres, he stops… We rarely see the contact sheets of a photographer. We only see the chosen photograph. We don’t see what’s before and after. Why do we do one photo instead of another? And then, why do we choose one photo over another? That’s what these “painted contact sheets” are saying.

At the very beginning of your enlarged contacts, you did not circle the photo. You only reproduced the act of circling the chosen pictures and the particular cross showing it on the contact sheet. But why did you have to go beyond, by putting paint instead of using a pencil?

I wanted to find a way to show this concretely, in a radical way, when I exhibited my images. I looked for several ways: pastel, colored pencils… I ended by finding what suited better, it was painting, by which I started my career. I don’t know if I can justify it differently… The combination of the “gesture of choice” on the contact sheets, the density of the paint, was for me a thing that could be “exhibited”.

You are unwavering in your commitment to film photography. Do you think revealing the frames before and after the decisive image in your contact sheets impacts people's appreciation of the often hidden, hand selection processes behind analogue photography?

To show the contacts is a way to give information. People can situate photos. They can understand, they can judge.

You have often favored the stark color palette of black, white, and red – what about this aesthetic appeals to you?

The red and the black. The red pencil is a kind of a cliché… something used by all photographers. There was no particular meaning except this one. The red and the black are two ways to communicate that suited me.

You've shot quite a lot of polaroids and instant photos, can you give us your thoughts on instant photography? What do you think sets it apart from other forms of photography?

When I started, instant pictures allowed me to do mockups, to easily conceive the pictures I imagined, in particular the fashion photos I did for Vogue. It was useful. And it gave me a lot of freedom to think, to conceive, to imagine. I regret to not have to keep all my instant photos of that time.

Do you plan on using your Lomo’Instant Wide? Do you have plans for another instant project generally?

Lately, I used the Lomo’Instant Wide a lot. Most of the time to take pictures of friends who come visit, or their kids playing. I noticed that instant pictures please children and young people a lot.

You once said ‘Almost everything is a coincidence, luck, and chance...half of everything I have done is done by chance’. Your discovery of blur in photography came about somewhat by a happy accident. Do you think it is important to leave room for such happenstance when making art?

Chance was of great importance to me. The ultimate goal of shooting is of course not taking blurry pictures… But I used these kinds of incidents, I assumed them. We always have to assume photographic accidents. To analyze them, to manipulate them, to enlarge them when necessary. Because we discover things we did not detect when shooting.

When photographing Harlem in the 50’s you said ‘The whites never go to Harlem, never even think of it, for Harlem lies off-limits, somewhere in the bad conscience of the city. Do you feel art/photography’s role is, in part, to disrupt the dominant political and social discourse?

Photography was a quite curious tool. In New York, at my beginnings, I realized that thanks to photography, I could become impregnated with the places and the people more easily than just by staring at them with my own eyes. Photography was a wonderful excuse to interact with people and my surroundings. Thanks to photography, I sometimes saw things I would not have never looked at otherwise.

Young boys wielding guns feature heavily in your New York book, a sign of the times. What recurrent imagery do you see on the street today do you feel encapsulates the current times?

When I looked at these photographs, ten or twenty years after, and when I still look at them, it always brings me back to my childhood memories. When I was a little boy playing in the streets with guns too. In my childhood scenarios, there were always stories of guns and ham thieves… In this famous photograph with the kids staring at me and pointing his guns towards my lens, I remember I said to him: “Go ahead, play it rough!”. And I remember that I was also playing it rough at that time… But I was also the shy one, the boy beside my main subject… I was also these people, also these kids at the same time. In the end, this photograph is two self-portraits in one single image. Of course, it was also a portrait of the street at that time, what it embodied. And I think that the street did not change that much… wherever it is.

New York, Paris, Rome, Moscow, Tokyo – how influential has this international travel been on your style and development as an artist?

The layout of my first book was directly inspired by a journal, a tabloid called “New York Daily News” and that was published every day in 3 million copies…That’s how I conceived all my other books, as an extension of a photographic journal across the globe.

May we know the story behind the photos selected for the camera?

One photo I used on the Lomo’Instant Wide is the baseball cards one. It’s part of the memories I cherish. Between kids, we were found of these baseball cards, these pictures of famous sportsmen that we bought, we traded, based on their rarity.

I also think of the end of the school day in Dakar in 1963. I had a photo mission to do in Africa for the British magazine “Town”. It was quite an innovative and trendy magazine from London and I collaborated with them because they enjoyed my book about New York. They had published my work about Tokyo and Moscow too. So one day, we pass by Dakar and we arrive at the end of classes. I improvised this photo. And I realized that the kids I was taking photos of and I had a quite similar idea of a portrait. They had to be as close as possible, they had to get inside the camera! I really like this childish aggression… But it’s a photo taken by accident. I was passing by, I came closer, and boom, the photo existed.

On the camera body, we often see photos of protests. I often took pictures of these events, mostly in Paris. What I liked about these, was most of all the availability of people. People, as I was saying before, it was like they had the same conception of photography as I did, something… aggressive. They got close to me as I was getting closer. I never had trouble taking photos as I wanted, photos very close, with a wide-angle. Nobody ever told me anything, nobody ever objected. Everybody accepted, it was implied.

We know that when you look at your photos from the past, you remember how you felt when you were taking them. Could you share with our readers how you felt when taking photographs with the Lomo'Instant Wide?

Instant photographs are, for me and for the people I take pictures of, a special experience. I really like the possibilities to share this moment, thanks to instantaneity. It’s not anymore solely personal. There’s nothing I like more than being able to do a photo on paper this way: take the photo and show it immediately. Moreover what’s funny is laughter. That sometimes mocking laugh, sometimes annoying laugh of the viewer in an exhibition when he sees an image and understands that the photographer succeeded… Instant photography allows us to directly discover the reaction. The viewer is caught in his own game.

You have said of wide-angle photography that it allows you to make one person feel that they are the center of your universe whilst also allowing you to capture everything around them too. What else do you particularly enjoy about wide-angle photography?

When I started, I only had two lenses: a 50mm and a 135mm. I was very frustrated with the 50 mm and the telephoto lens. I could not put enough things, not enough people in the photo. So I went to a shop and the salesman made me try a 28mm. I immediately went outside and started taking pictures, and I was able to get as close as I wanted to things and people, whilst adding all I wanted in the frame, whilst staying sharp. It was my beginnings with a 28mm, it was a good length. I don’t know if it still exists.

You took some photographs with a camera you bought from Henri Cartier-Bresson. Your styles are markedly different. To your mind, how much is down to the equipment and how much is the photographer?

Earlier in my time, I worked with a Rolleiflex that I won playing poker in the army. But I found that this camera did not meet my expectations, I liked more being able to look through the viewfinder at head height. So I indeed bought a camera from Cartier-Bresson. The fact remains that, every equipment is useful. We can easily obtain some stuff with a 6x6, some with a 35mm. The rest belongs to the photographer.

We all share a passion for photography and enjoy different aspects of it the most. For some, it’s being outside taking photos for themselves as a form of meditation, others do it for the moment of getting their photos back from the lab. What’s it for you?

I wanted to “own” what I was seeing. By accumulating documents about people I came across in the streets, or by combining people, objects around them, places… I was under the impression that I owned all that, that everything belonged to me, that it was mine. Later, the darkroom allowed me to express this ownership on a sheet of light-sensitive photographic paper. So, there was this relationship, and this “photographic shot” side that was not unpleasant. We point, we cock, we shot… And that’s it, to a certain extent, it’s like killing the subject by owning him, by freezing the subject in time and space. Do we not say “shoot” in English?

The 10 Golden Rules of Lomography express the very essence of our fun and experimental approach to photography. What do you think about the Lomographic photography approach and how does it differ to or relate with yours?

I think that "don’t worry about any rules" is one to keep.

Dare to be bold and own your art with the Lomo'Instant Wide William Klein Edition, now available at the online shop and partner stores.

Scritto da cielsan il 2020-12-14 in #cultura #news #persone #instant-photography #william-klein #lomo-instant-wide-william-klein-edition

4 Commenti